Sote was a Viking chieftain, who in the early 1000s is said to have been killed in a battle. The man who defeated him was the future Norwegian king, Saint Olaf. The event has been described in the story of King Olaf as recorded by the learned Icelander Snorre Sturluson in the early 13th century.

Figure 1: King Olaf II of Norway (Saint Olaf). Image on contemporary coins. Wikimedia/Public domain

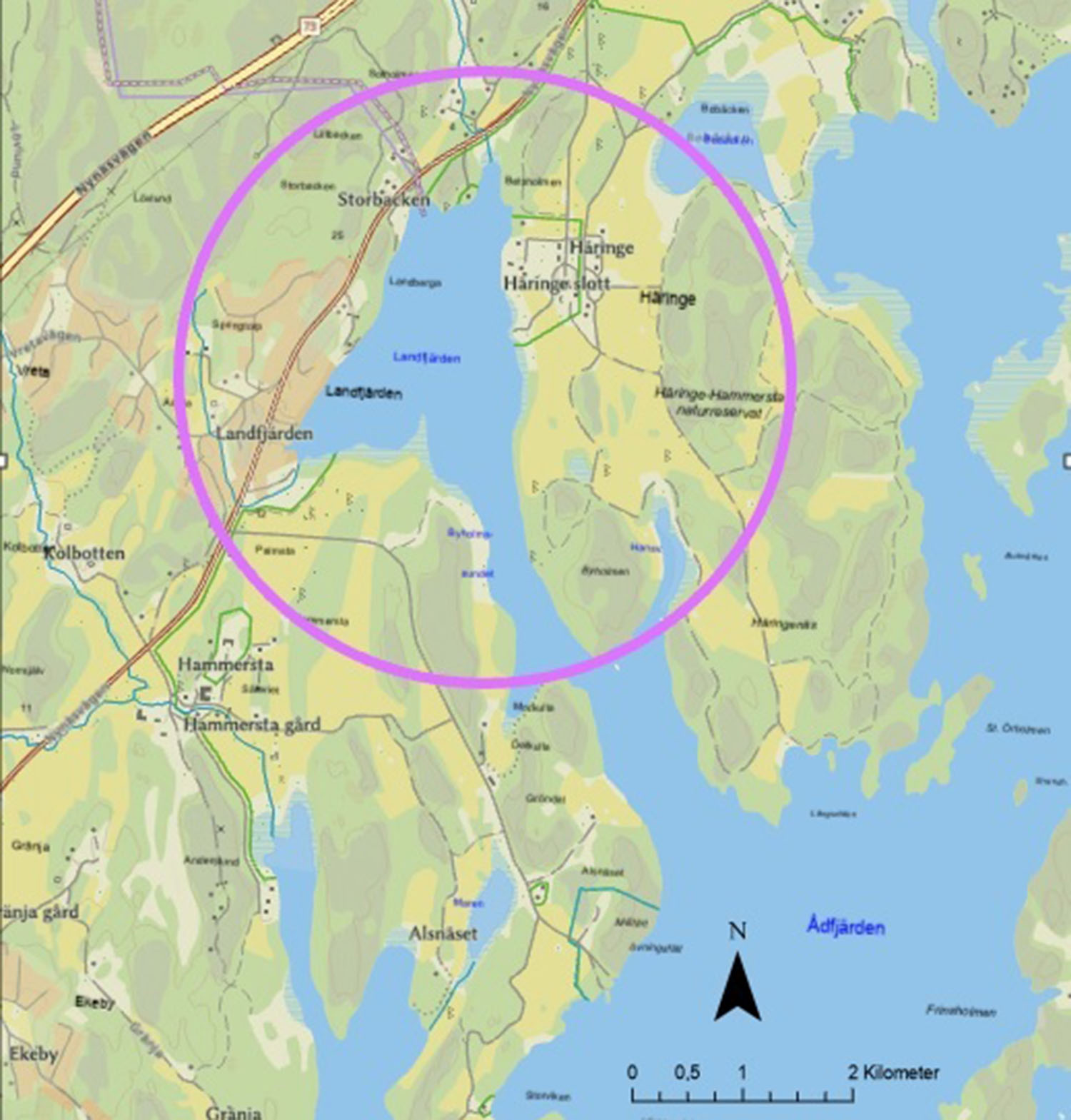

Snorre writes that Soteskär, where the battle took place, was “among the Svea skerries”. This is one reason why the incident was linked to the county of Sotholm on Södertörn and thus to Landfjärden and Häringe. The fact that the episode involving Sote and the battle is believed to have taken place here was proven back in the year 1800, during the Romantic period. This might be when the popular perception emerged that Sote lived at Häringe. This belief is still very much alive.

Figure 2: Map of Landfjärden and Häringe

Häringe is mentioned in writing for the first time in 1279. During the Middle Ages, the Häringe estate belonged to the church and later to the nobility. In 1495, Sten Sture the Elder took over Häringe, which then consisted of four farms. In periods, all or parts of the adjacent Hammersta estate were also included in the estate’s design.

In the 1600s, the current main building, Häringe Castle, was built. It was built by the owner at the time, field marshal Gustaf Horn. Today, the castle is run as a conference facility.

Figure 3: Häringe Castle. Wikimedia/Holger Ellgaard, CC BY-SA 4.0

Häringe also features the ruin “Sotes borg”, remains of a medieval fortified building or castle. The castle is said to have been demolished by the Danish king Hans, who burned down the city in 1502. The construction or use of the castle by a Viking chieftain can be ruled out. The name is a romantic construction, which was linked to the ruin later on. The same can be strongly suspected for the name “Sotaskär”, which is associated with the same place.

There is some uncertainty as to whether the history of Sote should be linked to Häringe and Landfjärden at all. In an older source from the 1100s, the site of Olaf’s battle with Sote is mentioned as lying “east in Viken”, in present-day Bohuslän. In Bohuslän there is also at least one Sotaskär, located in the Sotenäs district.

Regardless of whether or not Sote should be linked to Häringe, the area here has been farmed for a long time, at least since the Iron Age. This is attested to by several ancient monuments, including an ancient castle, burial grounds, graves and a rune stone. The surviving inscription on the rune stone reads: Björn let... Ulv, his brother. At the top is the preserved lower part of an equestrian motif, with the legs of the horse and rider visible.

Figure 4: Rune stone from the 1000s (SÖ 239) at Häringe. Wikimedia/Udo Schröter, CC BY-SA 3.0

On Landfjärden’s seabed, right next to Häringe, rests a handful of shipwrecks, several visible from the surface. It is long known that the wrecks were here. According to popular belief, they are remnants of Sote’s defeated and sunken ship. This view can also be determined to be a romantic idea from the period around the year 1800.

Figure 5: Landfjärden photographed from the site of the ruin “Sotes borg” (L2014:4192). Wikimedia/Holger Ellgaard, CC BY-SA 4.0

The age of the shipwrecks on the seabed and their use are not known. Part of our task in Häringe is therefore to document and take samples from the wrecks, to date them and determine what they were used for. Perhaps some of the ships were used for transport tied to the medieval estate? The initiative will preliminarily begin this autumn.

Figure 6: One of the wrecks in Landfjärden. Vrak/Håkan Altock

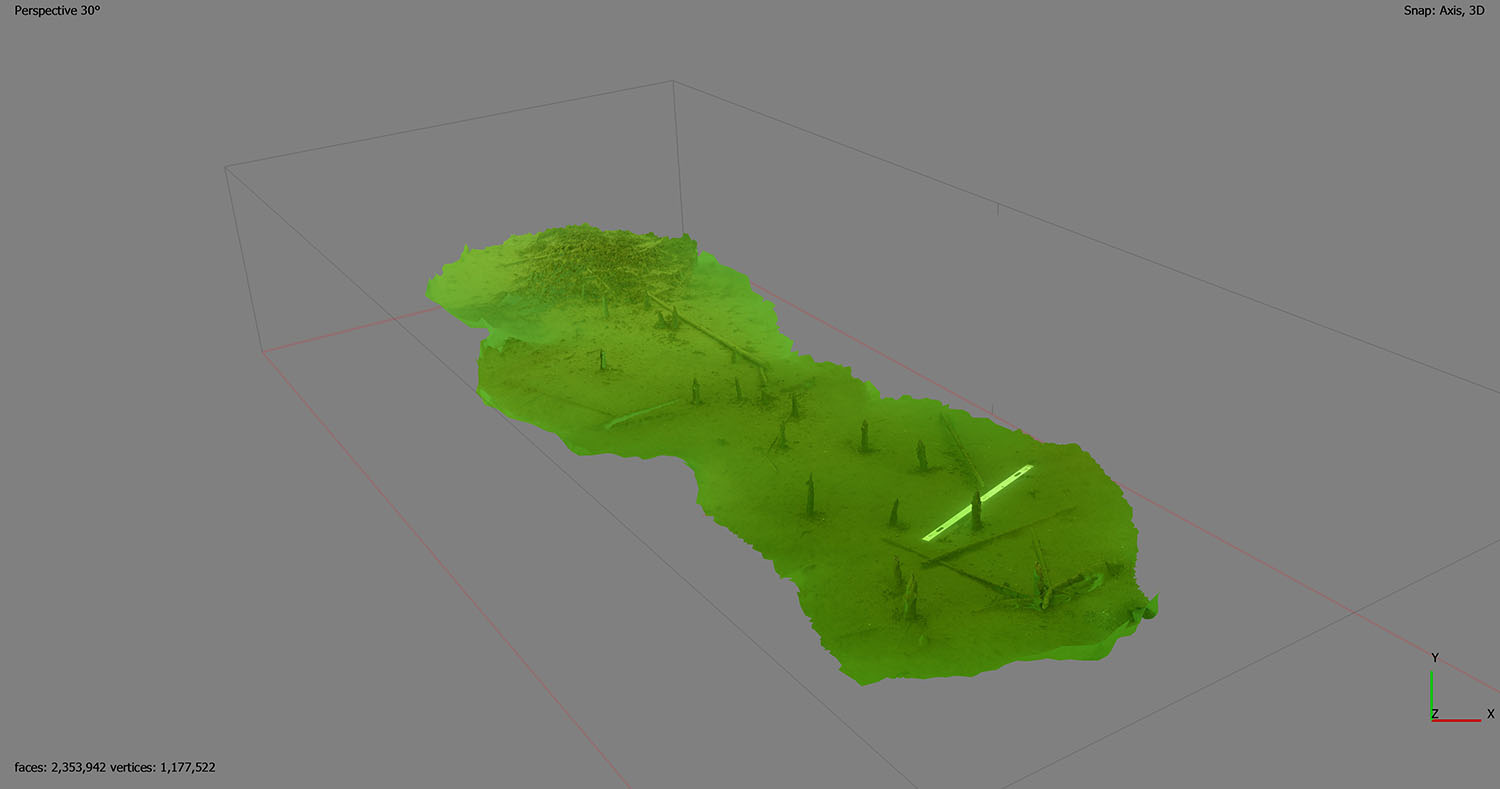

Another remain that was previously unknown is a pile barrier at the narrow inlet from the sea to Landfjärden. It consists of a large number of vertical wooden piles that are driven closely together into the seabed. In the past, the barrier prevented or obstructed the entrance to Landfjärden, and so protected the buildings that existed around it. But how old is it, and who or what should be associated with it? Another aspect of the museum’s work involves trying to answer these questions. Dives have already been conducted, producing 3D photo documentation of sections of the pile barrier and samples for dating. We are now eagerly awaiting the dating results and hope to be able to report back in the early autumn.

Figure 7: Section of the pile barrier, 3D model. Vrak