The Baltic Sea contains an estimated 300 environmentally hazardous wrecks, and of these, 30 need to have oil removed to prevent the risk of oil leaking into the sea.

In a lecture on environmentally hazardous wrecks at the Maritime Museum Studio led by museum director Mats Djurberg, Ida-Maja Hassellöv said we need to dig deeper than the surface. Hassellöv is an assistant professor at the Department of Mechanics and Maritime Sciences at Chalmers University of Technology.

“When we’re on a beach and see birds damaged by oil, we know it’s bad. But when oil leaks slowly from a shipwreck, we don’t know how microorganisms and small animals are being harmed,” Hassellöv says. “The waters are in quite poor condition, and the Baltic Sea is under strain.”

It isn’t just oil-filled shipwrecks that threaten the Baltic Sea. The bottom of the ocean is home to many ticking environmental bombs from modern times – mines and ships loaded with fertilisers and aviation kerosene, among other threats.

After World War II, the Allies sunk German warships in Skagerrak that were filled with both conventional and chemical weapons. Chemical weapons were also sunk off Bornholm and Gotland. Fertilisers, toxins and microplastics are other environmentally hazardous substances that end up in the Baltic Sea.

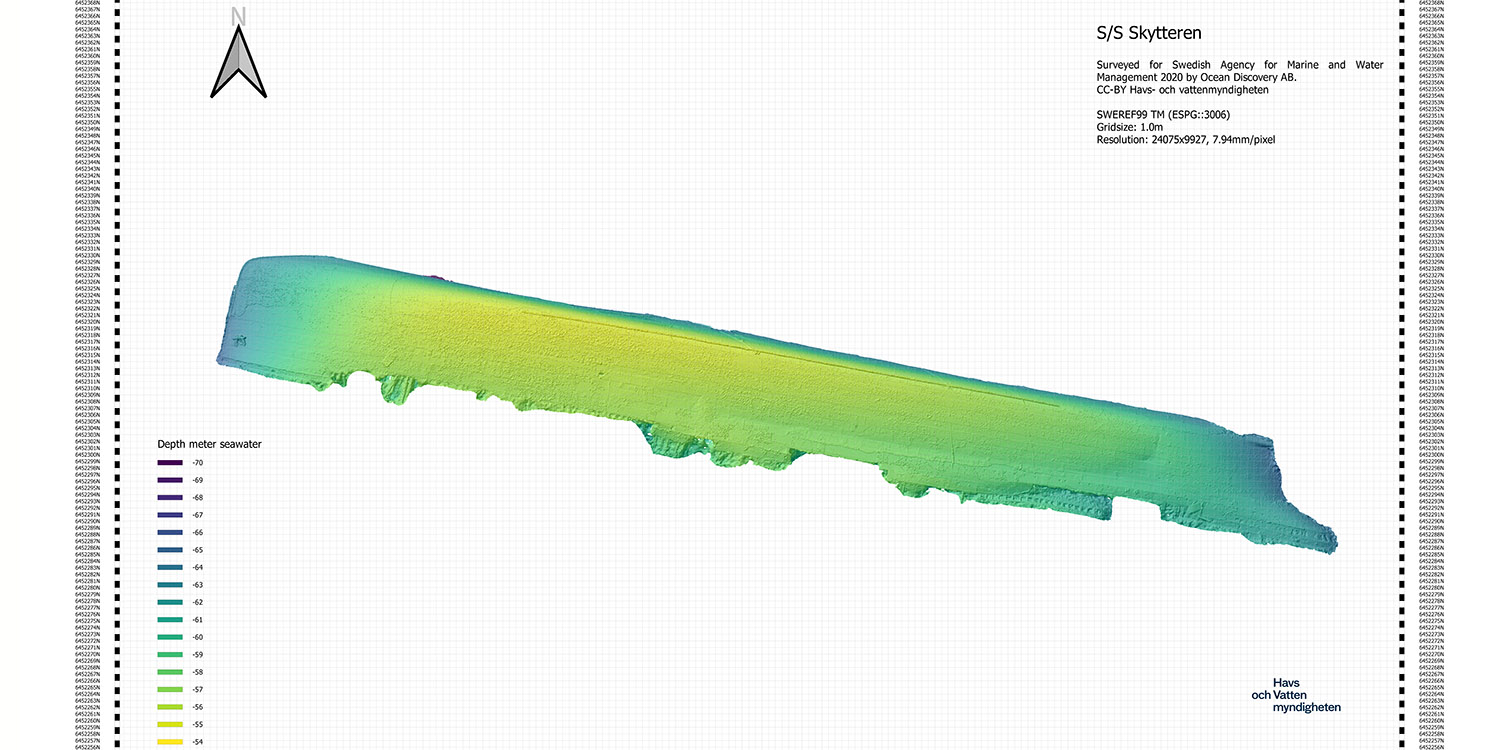

The oil spill from Skytteren became a wake-up call for a problem that had previously been overlooked. At its peak, the discharge totalled nearly 400 litres per day. No government authority was held responsible, and people soon realised that there were many more shipwrecks along Sweden’s coasts. The question was not if these would start leaking as well, but when.

The Swedish Maritime Administration was therefore tasked with surveying wrecks containing oil that needed to be removed. The museum’s maritime archaeologists provided information about which wrecks to prioritise. At the same time, Chalmers created a risk assessment model called “Vraka”, which could be used to calculate the probability of a wreck starting to leak.

“It costs a lot to clean up wrecks, but it costs even more to clean up beaches,” Hassellöv says.

In 2018, the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management was tasked by the government to clean up the highest priority wrecks within ten years. Oil has now been removed from some of the wrecks. But when wind turbines are built, for example, wrecks are on the high-risk list.

The wrecks are carefully examined before any oil is removed. With the help of photogrammetry, the ships can be studied in 3D, down to the decimetre, to understand what condition they are in.

Although progress is being made, there’s no time to lose. Environmentally hazardous wrecks are found all over the world. Sweden is farthest along in shipwreck decontamination efforts and is now helping other countries with its expertise in risk assessment.

Watch and listen to the conversation about environmentally hazardous wrecks! Guests include Ida-Maja Hassellöv, assistant professor at the Department of Mechanics and Maritime Sciences at Chalmers University of Technology, Fredrik Lindgren, investigator at the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, and Göran Ekberg, maritime archaeologist at Vrak – Museum of Wrecks. The conversation is led by Mats Djurberg, director of Stockholm’s Maritime Museum.